Verbal behavior seems like the newest buzz word in the world of Autism. Parents ask me almost every day what it is and how it is different from applied behavior analysis (ABA). Truthfully, it is usually used interchangeably. Technically speaking though, it is the part of ABA that teaches children how to use language to communicate.

Verbal behavior was developed by Skinner back in the 1950’s. Contrary to what many people think, it is not a new term. Truthfully in my personal opinion, which is not a popular one, behavior therapists are being forced to reconcile the dark history of applied behavior analysis and are using new words to create new connotations. Whether that is true or not, verbal is a critical instructional methodology for kids with Autism.

Children who have only a speech delay benefit largely from speech therapy. Speech therapy will help most kids who do not have any developmental delays with talking as long as they are physically able to. However, children with Autism require more than just speech therapy. That’s because children with Autism by definition have delays in all areas of communication. All people with Autism start off with communication delays. It is important to note that many people with Autism learn to communicate just as well as any neurotypical person. However, without delays in communication a person cannot get a diagnosis in Autism.

At this point, it is very important to understand a delay in communication is not the same as a delay in language. Language is vocal. Most of communication is non vocal. Early stages of communication includes eye contact, especially using eye contact to initiate and respond to joint attention and using gestures such as pointing. Reaching or grabbing for something or trying or bringing someone to a desired object is typically not considered communication.

Children with Autism do not use eye contact or gestures to communicate unless they are taught to do so in early childhood development. This is where applied behavior analysis comes in. Applied behavior analysis is most commonly known for its ability to address problem behavior. However, the truth is that in its initial applications, it was primarily used to show a person what a correct response is.

Let’s look at a very basic example of how that works.

Let’s say that an adult puts a button on the table in front of a child. The child has no idea what it is for. The child pressed the button and the adult gives the child a cookie. The child may not initially understand that he was awarded the cookie for pressing the button. However, if the same thing happened five times, eventually they will learn that when they press the button, they get a cookie. Now, whenever the child wants the cookie, they will press the button.

That’s how ABA works. Behaviors that a child does not know or understand are taught using a highly structured approach. A response is given, the child responds either independently or with help and the behavior is reinforced usually by a child getting an object that they desire. Eventually the child will learn to engage in the behavior and the reinforcement can be faded. Then the child can engage in the behavior independently.

Today applied behavior analysis has many practical implications. However, when using applied behavior analysis to conduct what it is commonly called verbal behavior or simply teaching a child to talk, this is the most basic application.

The main reason that parents seek out ABA is because they want their children to learn to talk. While this is not the only purpose of an ABA program, it is often the main component. Most often children learn language naturally by hearing others speak. But as stated earlier, children with Autism do not. They require language to be taught to them directly. ABA therapist break down language into some very basic components called operants. By teaching these operants or skills individually, ABA therapist can significantly increase a child’s ability to use language to communicate and after reading this section, so can you.

In behavior therapy, the verbal operants are: a mand, an echoic, a tact and an intraverbal. Once you understand each of these terms, it will be easy to tell them apart and you will know what to teach. In typical language development, they are learned in that order. However, from my personal experience, some children with Autism will follow the progression out of order. This is usually depends on what stimulus a child attends to, what lessons a therapist selects to teach first and whether or not they engage in vocal stereotypy.

Some children with Autism are very vocal even at a very young age. They will repeat almost anything an adult says or they will initiate words independently but they are out of context. These are vocalizations but may not be functional language. That’s why is imperative that a person understands verbal operants. The verbal operants provide a way to know if a child is truly communicating. The following section will explore the different types of verbal operants in detail and give examples of them.

A mand is in simple terms a request. The learner wants something, says what they want and gets what they said. It is triggered by a person’s desire for something. The fancy ABA term for that is specific reinforcement. This is the only operant where reinforcement is specific to what is said. Requesting is one of the main components of language. Children constantly ask for things. Requesting is the most motivating type of language and the one children learn first. Think about it, you get what you say. There is very real tangible consequence when you ask for something that is favorable. Therefore, it should be the first operant taught and initially the one that is focused on the most.

The second operant typically learned is an echoic. In this operant, someone says something that the learner repeats and the learner receives something unrelated to what is said. It is triggered by something someone else says. This is called nonspecific reinforcement. At this point, this probably sounds really confusing so let me give you an example to illustrate. A teacher says. “Say blue.” The child says, “blue” and the teacher says. “Great job.”

Sometimes it is hard to differentiate between mands and echoics when children are first learning mands because therapists will assist or prompt a child to give a correct response by telling them what to say. For example, if a child wants an apple and his therapist says, “say apple,” and the child says, “apple.” If the behavior results in specific reinforcement (the child gets the apple), it is a prompted mand, not an echoic. Echoics are mostly used in ABA to clean up pronunciations or to teach children to build upon their language by speaking in sentences. It can be an important part of an ABA program but it is the operant that occurs least often naturally in language.

The third verbal operant is a tact. A tact is when a person makes a comment about something they see, touch, smell, taste or hear. This operant is triggered by something in the environment. In order to be considered a tact, the comment must be made about something present. For example. “This tastes great.” “I see a yellow bird.” “I can hear a train.” Once again, reinforcement is non specific. Some tacts that someone may learn in ABA is to identify an object’s color, features, category, attribute or function. When visuals are used to teach this, such as books, puzzles or flashcards, it is a tact.

The final and fourth verbal operant is an intraverbal. This is the most natural conversational tact that is used in conversation. This is when someone makes a comment or asks a question based upon what another person says without the object they are discussing being present. For example, “What’s your name?” “My name is Jessica?” “My favorite color is pink.” “Cool, my favorite color is blue.” Intraverbals are similar to echoics in that another person triggers the behavior. But it is different because with intraverbals reinforcement is non specific. It is different from a tact in that there is no visual is present.

In order for anyone to have a fluent conversation, they must be able to use all four verbal operants. The next time you have a conversation, think about this final chapter. You will quickly notice yourself using all four operants in conversation.

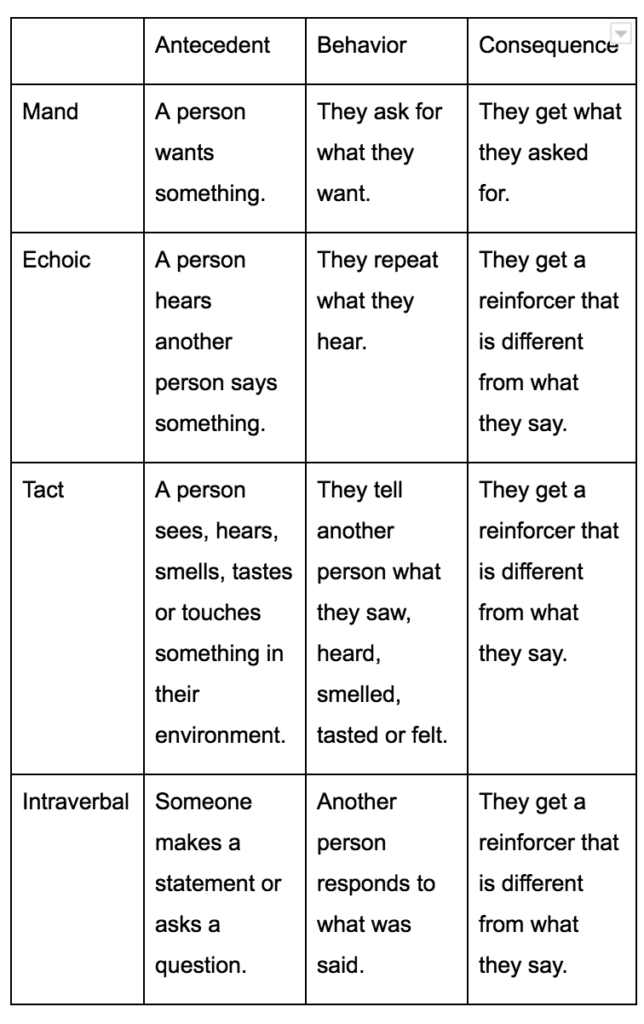

The following chart will summarize all the info above just to make sure it is really clear:

References

Cooper, J.O., Heron, T.E., & Heward, W.L. (1987). Applied Behavior Analysis.